Battle of Hartsville Tour

Step back in time and explore the rich history of the Battle of Hartsville. Our tour page offers a fascinating journey through the key sites and stories of this pivotal Civil War battle. Discover detailed narratives, historical landmarks, and immersive experiences that bring Hartsville’s heritage to life. Join us on a tour that honors our past and deepens your connection to the history of our town.

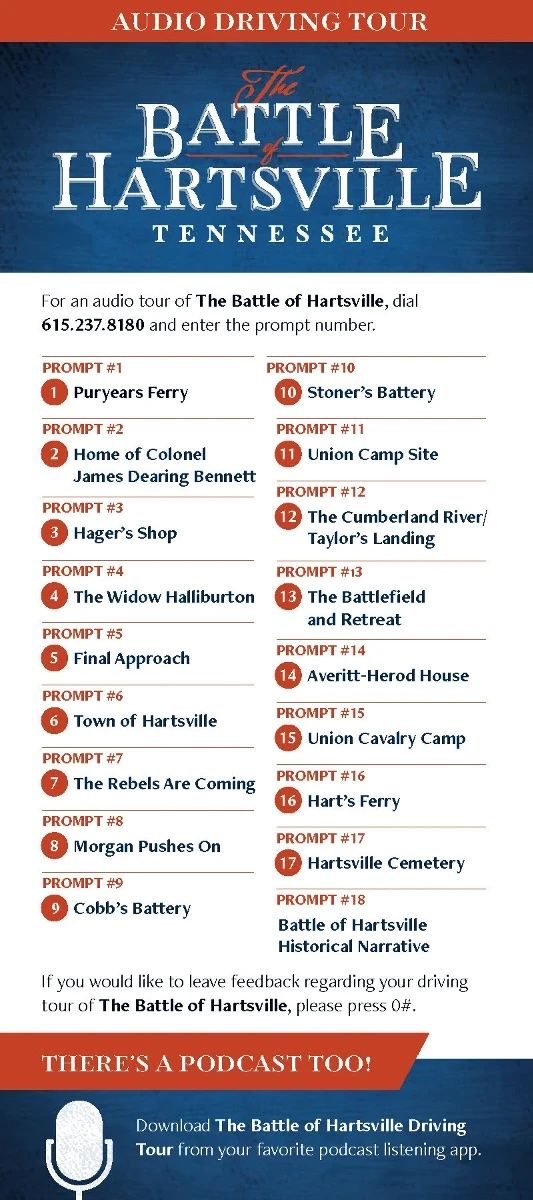

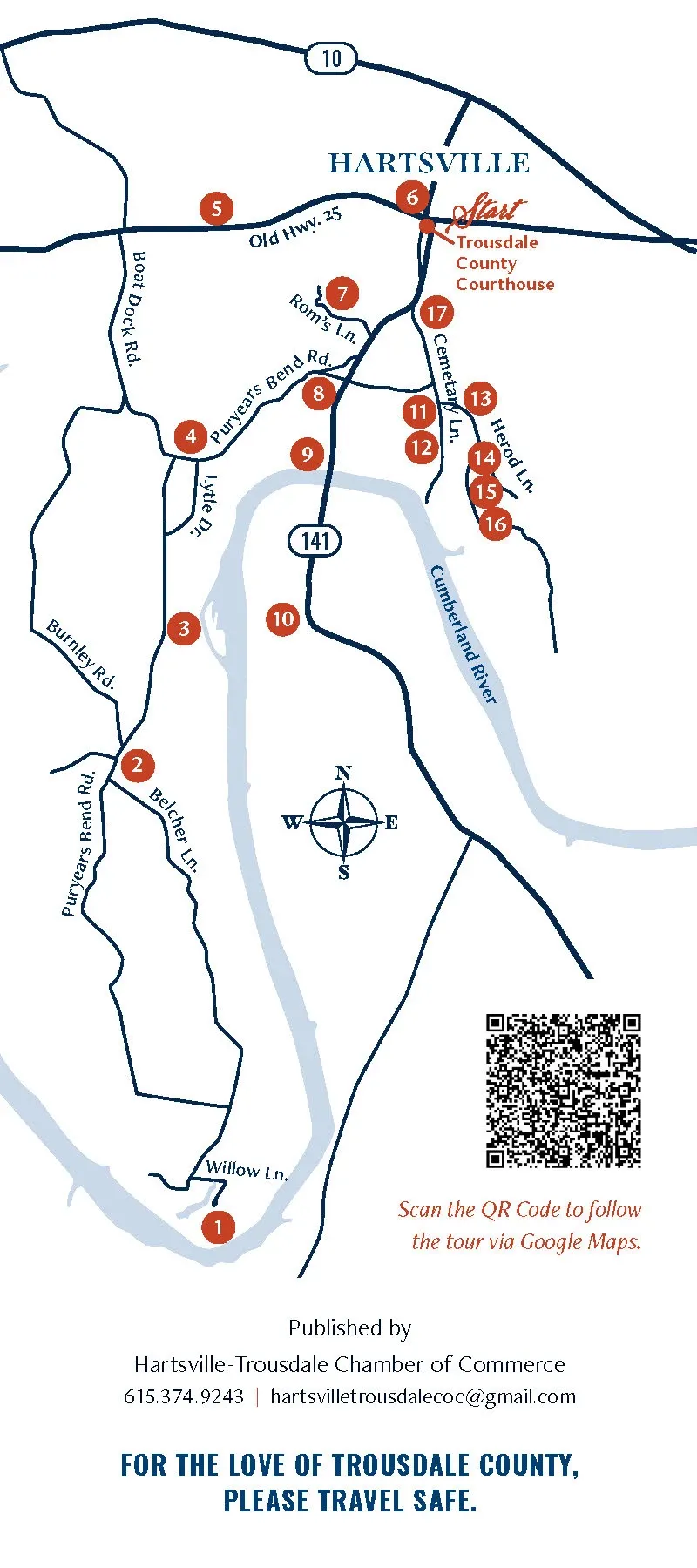

Discover the Story Through Our Audio Tour:

- Simply dial 615-237-8180 and enter the prompt number. Follow the audio tour prompts found below.

- Or download the Battle of Hartsville Podcast.

Colonel John Hunt Morgan and his troops arrived from Lebanon at Puryears Ferry in the dark of night at 10 p.m. on Saturday, December 6, 1862. With a plan to ford the Cumberland River in five hours, Morgan assembled his Artillery, Infantry, and a small part of the Cavalry on the south side of the river. He began the difficult task of moving horses, heavy cannon, and men across the icy Cumberland in two old leaking flat boats that had been arranged by his network of spies and supplied by a local sympathizer, 74-year-old Oliver Goldsmith “Ollie” Dickerson. The conditions were harsh, and the men being carried across by boat were forced to constantly bail water to keep from being swamped. The crossing took seven hours instead of the allotted five. Realizing early on the crossing was taking much longer than planned, Morgan directed Colonel Basil Duke and his Cavalry to continue on several miles further down-river to cross. The location was not ideal. A narrow bridle path provided the only access to the river. With each mount and man going down the slippery path, led by Col. John Dearing Bennet’s 9th Tennessee, the men plunged intothe river from the four-foot ledge above the river. Most of the Confederate men became completely submerged in the freezing water. The first men across built fires to warm themselves, but 15 men were so badly frozen they had to be left behind. By 3:00 a.m. with fewer than half his men across the river, Duke realized he must hurry to meet Morgan at the rendezvous point. He was forced to leave the other half of his men on the south side of the river with orders to hurry on.

> Go back the way you came and stay to the right until you reach Stop 2.

Down the winding path to your left, Colonel John Bennett’s homesite sits just out of view toward the back of the property. Colonel Bennett was the Commander of the 9th Tennessee Cavalry made up of local men from Hartsville, Coatstown (now called Westmorland), and Richland (now called Portland). It is believed that Bennett and Colonel Morgan stopped at Bennett’s homeplace for breakfast on their way to the pre-determined rendezvous point with the rest of Morgan’s troops. Known to be a fine commander respected by his men, Colonel Bennett died seven weeks following the Battle of Hartsville from typhoid-pneumonia on Morgan’s second Kentucky raid in Elizabethtown, Kentucky on January 23, 1863. His body was transported back to Hartsville by his faithful servant, Jeff, and buried here. Fourteen years later his widow, Martha (Hutchison), had his body reinterred in the Hartsville cemetery (stop 17). She also honored her husband’s promise to his servant Jeff and deeded 60 acres of land to him free and clear once the war ended.

The blacksmith shop of Andrew Jackson “A. J.” Hager once stood in the empty field on the right. This was the planned rendezvous point for Morgan and his men. Traveling 30 minutes from Puryears Ferry, Morgan arrived about 5:30 a.m. with Colonel Thomas Hunt, Commander of the Infantry. Colonel Duke arrived at the rendezvous point only minutes after Morgan and Hunt due to the additional time it had taken him and his men to find a suitable ford to cross the Cumberland. At this spot, Colonels Morgan, Duke, and Hunt prepared their final plans for their attack on the Union camp, just two miles away to the east.

> Continue ahead and take the first right, Lytle Drive, to the end.

The home and burial site of Letty Halliburton was on this hillside straight ahead. Letty Halliburton was instrumental in helping many of the wounded after the battle. A yellow flag flew above her home, identifying it as a refuge for the wounded. After the battle, Union troops loaded wagons with wounded soldiers and brought them to Halliburton’s home. She used her entire supply of bed linens as bandages for the wounded. Dr. John Orlando Scott, of the 2nd Kentucky, and the only Confederate surgeon left behind after the battle said, “It is a grand site to see the men in blue assisting his brother in gray in all kindness and affection.”

> Turn left out Boat Dock Road, 1.3 miles, to Old Hwy. 25 and turn right, 0.2 miles, to Stop 5.

After leaving Hager’s Blacksmith Shop, Morgan detached part of Col. Bennett’s 9th Tennessee Cavalry to set up a roadblock on the Hartsville-Castalian Springs road and other points to cut off any escape Union troops might try to use. Bennett took the rest of his regiment to Hartsville one mile away. Morgan and the rest of his troops crossed here through the lowest point and made their initial approach toward their objective, still undetected by the Union troops.

> Head straight into town.

The remainder of Colonel Bennett’s Cavalry made their way into town. The 9th succeeded in capturing 450 Federals, including Co. A, 104th Illinois, who were posted here to guard the town. The Union soldiers had occupied many buildings in town including the Locke Hotel on the corner of Main St. and Broadway at the site of the old Bank of Hartsville building. Two buildings used as hospitals still stand today. At the corner of Church and West Main stands the Hager building (now Total Image), built in 1838. This building housed the bed patients. Behind the Hager building on Church Street stands the old Methodist Church, built in 1843, soldiers with less severe wounds were treated here.

> Get out and stretch your legs. Look around Historic Hartsville. Next drive back out Hwy 141 S (River Street), 0.6 miles, turn right on Rom Lane to Stop 7.

As Morgan approached this hill from the valley between the two hills to the northwest, he sent a small force disguised as Union soldiers to capture the pickets stationed north and west of the Union’s Infantry camp. The reserve pickets observed this and fired the first alarm to the Union camp, as Morgan approached with his main task force and artillery from the northwest. Morgan dispatched Colonel Cluke’s and Colonel Chenault’s Cavalry units toward the camp while he accompanied Colonel Hunt and Cobb’s Battery southward to occupy a position to observe the Union camp and make adjustments to their artillery firing on the Union troops.

> Follow this drive to the end and turn left.

At this point Morgan’s Infantry and Cavalry spread out and deployed on a low ridge overlooking the Infantry camp. The Cavalry dismounted (Morgan’s Cavalry often fought as Infantry) and moved to the left to flank the Union troops. The Infantry pushed onward toward some 2,100 Union troops who had formed on a line of defense on the hill behind the Trousdale Highway Department Garage. The Union Artillery stationed on this hill was forced to move back to the bluff on the river. The fiercest part of the battle was fought here.

> Go to the river, 0.4 miles.

Here across the ravine, high atop this hill behind the water plant, and to the right, Colonel Robert Cobb’s Battery set up for the Confederates’ Artillery assault on the Union camp upon the hill to your left. As Colonel Morgan stood there during the battle, one caisson was destroyed by a direct hit from the Union cannons, killing David Watt who was sitting upon it. Colonel Morgan’s young aide, William Craven Peyton, was mortally wounded. He was taken to the home of a Mrs. Lee, where he died of blood poisoning.

> Cross the river bridge.

Here on the south side of the river on the elevated ground to the left, Confederate Major Robert G. Stoner set up his battery of two mountain howitzers. Knowing that these guns would not reach the Union camp, his job was to keep the Union troops wondering if they would. Afterwards, Stoner’s men forded the river several times, bringing a prisoner back across each trip. The back side of the bluff to the right was the camp of the Union Army. The ridge ahead and to the left is Stop 7.

> Go back across the river, 0.6 miles, then turn right on Cemetery Road, 0.5 miles.

This is the site of the Union troop’s camp. The Union garrison of the 39th Brigade, 12th Division, under the command of Colonel Joseph R. Scott, arrived here from Tompkinsville, Kentucky, via the Goose Creek Valley on November 28, 1862, to relieve Colonel John Marshall Harlan. Harlan, who later became an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, of the 10th Kentucky Infantry, commanding the Second Brigade, 1st Division, had been in Hartsville about two weeks. Colonel Scott’s forces consisted of the 104th Illinois Infantry, 106th and 108th Ohio Infantry, 2nd Indiana Cavalry, Co. E. 11th Cavalry, totaling 2,400 men. On December 2, Colonel Absalom B. Moore of the 104th Illinois, and ranking officer, was directed by the Union commander to relieve Colonel Scott who had been called to Nashville. Here at the Union camp site a large part of the fighting and surrender of the Union garrison took place, just 75 minutes after the battle began.

> Go to the end of this road.

Time was of the essence following the Union’s surrender. Aware of Union reinforcements advancing from Castalian Springs, Morgan and his men loaded as many empty wagons as they could manage with confiscated Union supplies. They discarded their Austrian rifles and muskets in favor of the Springfield rifles that had belonged to the Union troops. Morgan then directed his men and prisoners to cross the ford known then as Walker’s Landing, now known as Taylor’s Landing, while he directed the wagons and cannons to cross a half mile up the river at Hart’s Ferry (Stop 16). Imagine rushing from the battle field to cross this river for the second time in less than 12 hours—in chest-deep, icy water with a several inches snow on the ground, in the bitter cold with two to three men on horseback. It was done with success.

> Turn around, go 0.3 miles then turn right on Herod Road.

In the far distance to your right, a clear view in winter, sits the Union camp and battlefield. Across these ravines, some 4,000 men, both Union and Confederate soldiers, were making quick time to leave this area before Colonel Harlan arrived with thousands of Union reinforcements from Castalian Springs some nine miles away.

Atop the hill to your left overlooking the battlefield, sits the beautiful home built by Peter Averitt, Sr., around 1834. During the battle, Peter’s son, Richard, and his family lived here. According to tradition, wounded Confederate soldiers were brought here to be cared for after the battle, and it was where Colonel John M. Harlan pardoned them. There is a large bloodstain resembling a man’s face in the floor on the east side of the house. The house is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Union’s 2nd Indiana and Co. E. 11th Kentucky Cavalry camped and were positioned in this area to guard Hart’s Ferry. The entire Union Cavalry force moved up to this location to support the Infantry but participated very little in the battle. They suffered only three casualties, and most escaped capture.

> Drive to the curve in the road.

Located some 400 yards from here at the river, Hart’s Ferry was started in 1798 by James Hart (from whom Hartsville was named). From here, Colonel Morgan began his exit from Hartsville with all his captured goods, two pieces of artillery, ammunition, supplies, and wagons. Just as Morgan was getting the last of his men across the river, Union Colonel John M. Harland arrived from Castalian Springs and opened fire but did not pursue them. One of his cannon shots barely missed Morgan and his staff, hitting a tree limb above them. The Union reinforcements destroyed three wagons in the river as the Confederates made their exit from Hartsville. The Union losses were 58 killed, 204 wounded and 1,834 captured. The Confederate losses were 21 dead, 104 wounded and 14 missing in action. For his daring victory, John Hunt Morgan was promoted to brigadier general. The battle was considered Morgan’s greatest victory and is considered by many as the best executed and most successful cavalry raid of the Civil War.

Finally, you have reached the Hartsville Cemetery, the final resting place for over 50 Confederate veterans. Among them is Colonel James Dearing Bennett, Commander of the famed 9th Tennessee Cavalry. After the battle, Winslow Hart (the son of James Hart) and other citizens buried both Union and Confederate casualties on a knoll at the rear of the cemetery. Some of the Union dead were later moved and returned to their homeland or reinterred at the National Cemetery in Nashville.

Uncover the Rich History of the Battle of Hartsville

In the fall of 1862, the large, well-equipped Union Army occupied Northern Tennessee. While both sides continued to battle, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee were sites of early defeats for the Confederacy. Confederate Raider John Hunt Morgan, who sought to disrupt Union supply lines, had led several successful skirmishes in the upper Middle Tennessee area.

In the fall of 1862, the large, well-equipped Union Army occupied Northern Tennessee. While both sides continued to battle, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee were sites of early defeats for the Confederacy. Confederate Raider John Hunt Morgan, who sought to disrupt Union supply lines, had led several successful skirmishes in the upper Middle Tennessee area.

Several times, he had ridden and camped in the Hartsville area, where he was always warmly received by the citizens. While in Hartsville several months before the battle, Morgan had one of his men, Gordon E. Niles, a New Yorker with publishing experience and loyal to the Southern cause, take command of an abandoned printing press and publish a newspaper, the Hartsville Vidette, on August 16, 1862 (it is still in publication today).

As events unfolded in Tennessee, the Cumberland River became a natural boundary separating the Union and Confederate squads, with the Union Army occupying the areas north of the river (Carthage, Lafayette, Gallatin, Castalian Springs, and Hartsville) and the Confederated holding the areas south of the river (Lebanon, Sparta, Baird’s Mill, and Murfreesboro).

While in the Murfreesboro area with the Army of Tennessee, Colonel Morgan learned of the Union’s strong garrisons in those areas to the north, including the town he was quite fond of, Hartsville. The elevation of Hartsville provided a great overlook of the river, allowing the troops to see for miles in the direction of the enemy. It also allowed them to overlook the town, and the river could be easily forded in that location. Hartsville was an essential location for both sides to hold. At Hartsville, Col. Absalom B. Moore of the 104th Illinois was in command of the Union 39th Brigade, 2,400 men strong, consisting of the 106th and 108th Ohio Infantry, 104th Illinois Infantry, 13th Indiana Artillery, 2nd Indiana Cavalry, and a portion of the 11th Kentucky Cavalry. General Eleazar A. Paine was Union Commander at Gallatin, with troops numbering 6,000.

General Paine had a reputation as a ruthless commander. Morgan had learned of his hard-hearted tactics in dealing with Southern sympathizers, making him anxious to retaliate on behalf of the Confederacy. Aware that Paine’s command was too large for him to defeat, Morgan decided instead to attack Colonel Moore’s command in Hartsville, which his spies had estimated at 1,500 men. Morgan felt strongly he could approach Hartsville from his location in southern Wilson County, overtake the Union camp quickly, destroy the Hartsville garrison, and earn a much-needed victory for the Confederacy. He would later discover that his spies had wildly miscalculated the number of troops camped at Hartsville.

As his men were resting at Baird’s Mill nine miles south of Lebanon in southern Wilson County, Morgan traveled to Murfreesboro to urge General Braxton Bragg, whose command had withdrawn from Kentucky to Middle Tennessee, to sanction an attack. After careful thought and Morgan’s persistence, Bragg approved his proposal to cross the Cumberland and hit Hartsville. After being allowed to select two infantry regiments containing some 700 men from Colonel. Roger W. Harrison’s Kentucky Brigade, Morgan chose the 2nd and 9th Kentucky under the command of his uncle, Colonel Thomas H. Hunt, and Cobb’s Battery. His men consisted of the 7th, 8th, and 9th Tennessee Cavalry a group of local men commanded by Hartsville Colonel James D. Bennett. Morgan’s Cavalry for the mission was commanded by his brother-in-law, Col. Basil W. Duke, including two of Morgan’s Kentucky Batteries, Stoner’s and Corbett’s; Morgan’s forces totaled 2,100.

On Saturday morning, December 6, 1862, Morgan and his command left Baird’s Mill at 10:00 a.m., with only the officers knowing their destinations. There had been a drastic change in the weather that week, going from fall-like temperatures to snow, ice, and frigid cold temperatures, making the crossing more complex and the Union camp less vigilant against an attack. The Confederate troops traveled eight miles through the snow and sleet before stopping in Lebanon about 2:00 p.m. to rest and eat. As they left Lebanon, the men were told of their destination—Hartsville. Excitement spread throughout the ranks as they continued their long march toward Hartsville, some 17 miles away in the icy conditions.

Arriving at the Cumberland River at 10:00 p.m., they began their crossing of the cold, dark water. Taking longer than expected to cross the Cumberland, Colonel Morgan, the Infantry, Artillery, and a small part of the Cavalry crossed at Puryears Bend. The remaining majority of the Cavalry led by Colonel Basil W. Duke traveled a few miles further to find another ford across the river, and this caused a dangerous delay. Daylight was breaking, and the element of surprise was quickly slipping away. Colonel Duke was forced to leave many of his Cavalry units, which were still crossing the river behind, so he could rush to meet Morgan at their planned rendezvous point. Because of the complicated river crossing, Morgan’s force was now reduced to 1,300.

Colonel James D. Bennett and his 9th Tennessee Cavalry were sent into town to cut off any escape the Union troops might take. As they approached the Union camp, a small group of Morgan’s commanders disguised in Union uniforms captured the first Union pickets. Their backups fired shots at the fast-moving Confederates and prevented their surprise attack. The cry was heard, “The Rebels are coming!” Soon, it became apparent by the glow of campfires that the Union numbers were much more significant than initially anticipated. Colonel Duke exclaimed to Morgan, “You have more work cut out for you than you bargained for.” Morgan answered, “Yes, and you gentlemen must whip and catch these fellows and cross the river in two hours and a half, or we’ll have six thousand more on our backs.”

They were victorious in their efforts. In just 75 minutes, Morgan’s men out-maneuvered, out-flanked, and out-fought the Union troops, defeating a much larger force than their own. Union losses were 58 killed, 204 wounded, and 1,834 captured; total casualties were 2,096. Confederate battle losses were 21 killed, 104 wounded, and 14 missing, for a total of 139 casualties. Hurrying to re-cross the Cumberland (for the second time in less than nine hours), Morgan successfully transported his men, prisoners, and the captured supplies back across the icy water before the Union reinforcements at Castalian Springs could arrive.

In Nashville, a telegram arrived from the General-in-Chief in Washington D.C., “The President (Abraham Lincoln) directs that you immediately report why an isolated brigade was at Hartsville, and by whose command; and also, by whose fault it was surprised and captured.” Not receiving an appropriate answer, the General-in-Chief said, “The most important of the President’s inquiries has not been answered. What officer or officers are chargeable with the surprise at Hartsville and deserve punishment?”

Morgan and his men were well received and honored by many local citizens along the route as they traveled back to Murfreesboro with their captured wagons, arms, and supplies. The victory was a much-needed boost to the morale of the Confederates. Morgan was highly praised for his victory and received congratulations from the Confederate Congress. Confederate President Jefferson Davis arrived two days later and promoted Morgan to brigadier general. During his visit, Davis was presented with the captured Union Infantry colors. General Bragg also complimented the entire command and ordered that the name “Hartsville” be inscribed on the banners of all regiments participating.

Perhaps Colonel Basil Duke summed up the Battle of Hartsville when he said, “This expedition was justly esteemed the most brilliant thing that Morgan had ever done and was referred to with pride by every man in it.”