Trousdale County Attractions

Explore the diverse attractions that make Trousdale County a unique destination. From scenic outdoor spots and historical landmarks to charming local spots and recreational activities, our Attractions page highlights the best of what Trousdale County has to offer. Discover the hidden gems and must-see places that will make your visit to Hartsville unforgettable.

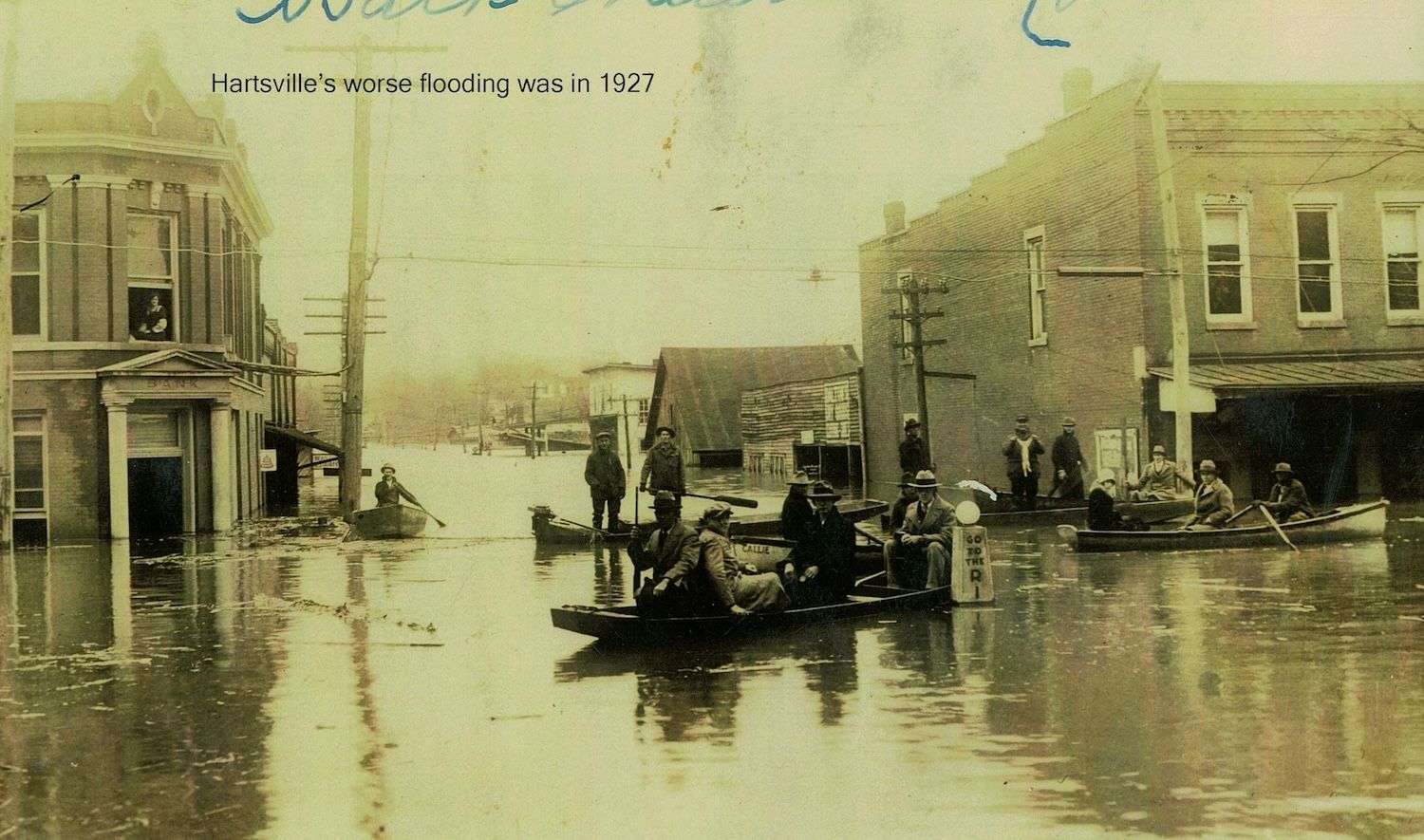

We have a rich history in Hartsville, TN. Tobacco fields, floods, civil war camps and battles, visitors of royalty, and so much more.

Home of the Trousdale County Museum and Chamber of Commerce and built in the 1800s, the Hartsville Train Depot has now been fully restored. The Depot offers much history of not only days of the railroad, but also many other interesting items.

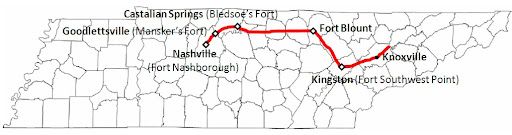

In an effort to encourage settlers to move west into the new territory of Tennessee, in 1787 the mother state of North Carolina ordered a road to be cut to take settlers into the Cumberland Settlements – from the south end of Clinch Mountain (in East Tennessee) to French Lick (Nashville). A hunter, Peter Avery was selected to direct the blazing of this new trail through the wilderness. The trail was laid out following buffalo trails which the Cherokee Indians had frequently used as a war path. It led from Fort Southwest Point at Kingston through the Cumberland Mountains up into what is now Jackson County, to Fort Blount. From there it rambled along through the hills and valleys of upper Middle Tennessee to Bledsoe’s Fort at Castalian Springs, then to Mansker’s Fort and finally to Fort Nashborough. These five forts provided shelter and protection for travelers along the Trace.

In 1787, the Assembly of North Carolina provided that 300 soldiers would be available for protection at the Cumberland Settlements. These soldiers assisted Avery in laying out the Trace, each soldier being paid with a land grant of 800 acres for one year’s work. A 10 foot wide trail was cleared, and in that year 25 families traveled along the new road. By 1788, the “Trace” was still merely a rough trail marked by trees scored (or “blazed”) to guide the pioneers and travelers. For several years, only pack horses could follow the rugged trail, and journals of many travelers along the Trace detail hardship encountered as they journeyed for several days to make the 300 mile trip. At this time the Trace was called the “North Carolina Road” or “Avery’s Trace”, and sometimes “The Wilderness Road”.

A portion of the Trace passed through Cherokee land, and the Cherokees demanded a toll for use of the road. Disputes inevitably arose over the toll, and in spite of a treaty designed to settle these disputes, war was declared. As a result, 102 travelers along the road were killed. Finally, North Carolina legislature ordered that militia details of 50 men each would be kept in readiness to escort travelers when large enough groups had gathered at the Clinch River to head west. At the beginning of the Trace, at the Clinch River, a blockhouse was built in 1792. Territorial Governor William Blount placed much of the territorial militia on active duty under the command of General John Sevier, who based his operations at the blockhouse and began to provide the armed escorts for travelers along the Trace.

The Trace was widened into a wagon road by order of North Carolina legislature a few years later. Funds to pay the cost of developing Avery’s Trace into wagon road were to be raised by a lottery. As a wagon road, however, it still offered very difficult traveling! Travelers were advised to keep a close watch on their horses, which were occasionally stolen along the way by Native American hunters. By this time, the war over the territory had ended, so travelers no longer feared for their lives along the Trace, but they did have to watch their horse!

By the late 1790s, road conditions varied from “bottomless” to “fine and dry”. Wagons often sank to their axles in mudholes. At places the Trace was covered with stone slabs which made it difficult for horses. Much of the way was passable only on foot. Rivers and streams had to be forded in several places. At Spencer’s Mountain the road became very steep and full of rock slabs. It was reportedly so bad that wagons could not go down the mountain without the brakes on all wheels and with a tree hung on behind to slow them down. The mountaintop was said to be “quite denuded of trees”. Accommodations for travelers were almost nonexistent. One traveler recorded that, “The houses are so far apart from each other that you seldom see more than two or three in a day.”

As rough and difficult as the road was, it was the major passage to the Cumberland Settlements. Lone travelers, or pioneers families would load their possessions onto their wagons and meet fellow pioneers at the Clinch River. Imagine the excitement in the air as they milled about, waiting for the moment of their departure, talking about what they would find at the end of the trial, saying their last-minute goodbyes to friends and family, promising to send letters as soon as possible. When they had gathered, a militia detail would join them. They would climb into their wagons, wave goodbye and drive their horses into the Clinch River, starting on their journey into the unknown wilderness, leaving behind family and friends and their ties to civilization. Many felt that they would reach paradise or “the promised land” at the end of their journey; many sought lands they had been granted for service to their new country. For whatever reason they came, they faced a long and difficult ride along a long, winding, and torturous trail. There were hazards at every turn, and almost no accomodations for the weary travelers. They camped along the way, cooking over campfires and sleeping under the stars. As the days wore on, they were occasionally fortunate enough to find families living along the Trace to give them shelter and food for themselves and their horses, but these were few and far between, and they were sometimes charged hefty prices for these accomodations. The land they traveled through was rich and beautiful – hills and valleys full of canebrakes, giant trees and tangled vines, rolling into the distance in every direction. But, it was described as 300 miles of wilderness by many of those who made the journey – a wilderness inhabited by wolves, mountain lions, coyotes, deer and buffalo herds in tremendous numbers. As groups of pioneers traveled along the Trace, they began to seperate and go in the directions of their individual land grants or in search of adventure along the way. As they reached the last fort, Fort Nashborough, often just the military remained. These soldiers usually joined another group of settlers going back east. It was reported by one traveler that families were constantly moving in and out of the area, “back to whence they came or onward to other settlements. Thus to spirit of wandering is in the people…”

Many notable people traveled along the Trace, among them Andrew Jackson, Judge John McNairy, General William Davidson, Governor William Blount, The Duke of Orleans (who later became King of France), Bishop Francis Asbury, French botanist Andrew Michaux, Judge Archibald Roane, Thomas “Big Foot” Spencer, and many others. The Trace now stands as a testament to the many travelers and families who had the courage to undertake such an arduous and difficult journey, searching for a new life for themselves, their families and their future generations.

Currently, there is an Avery Trace Welcome and Visitor’s Center located just inside the upstairs courtroom in the Trousdale County Courthouse. Anyone interested in learning more about the Avery Trace is invited and encouraged to visit the Avery Trace Welcome Center.

Welcome to Hartsville, Tennessee, the location of what many have called the ‘most successfully executed cavalry raid of the war between the states,’—The Battle of Hartsville. While the number of troops engaged in this battle was comparatively small, the Confederate victory was so complete and decisive in military tactic that news of the battle was reported across the country by nearly 70 newspapers. In fact, the Battle of Hartsville attracted the attention of President Abraham Lincoln, who sent a telegram to the commanding senior general stationed in Nashville asking, “Who was responsible for the disaster at Hartsville?” Due to the success of this battle, Confederate Colonel John Hunt Morgan, known as “the Thunderbolt of the Confederacy,” received his commission to brigadier general.

This driving tour includes buildings and homes used as hospitals, sites where Morgan quartered nearly 2,000 prisoners after the 75-minute battle, river crossings, rendezvous points, and a cemetery. We hope you enjoy your tour through Hartsville, Tennessee.